Climate Change Strategies for School Gardens

Around the world, climate disruption is making large-scale agriculture, small-scale farming, and even backyard gardening less predictable and reliable. School gardens will not be immune.

Here are some climate change strategies for school gardens.

These strategies are adapted, with deep gratitude, from Resilient Gardens for a Changing Climate, a presentation by Linda Gilkeson, a master gardener living on the coast of southwestern British Columbia, Canada, in zone 8 (USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map for North America). But many of these strategies will be suitable for any zone or climate.

How do you feed the world without increasing emissions, fueling biodiversity loss and deforestation, or deepening inequality and poverty?

— Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

How we use land for food production also affects greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity, urban sustainability, human migration, and so many other areas. Food touches every part of human existence, providing a way of making people aware that how they eat can do much environmental good.

— Daniel Rubenstein, Princeton University

Pender Island School Garden (photo by Julie Johnston)

Pender Island School Garden (photo by Julie Johnston)Climate Change in the School Garden

School gardens, depending on their location, are sure to be impacted by:

- more extreme weather events (hail, for example; further examples below in parentheses)

- an increase in storm intensity (higher winds)

- changes in rainfall patterns (heavier deluges or longer dry periods)

- increased severity of heatwaves and cold snaps (with higher or lower temperatures than usual, sometimes out of season)

- increased risk of flooding and waterlogged soils

- an increase in pests

- perhaps even wildfires (the health effects of smoke while working outside … or worse)

Climate changes disrupt the seasonal adaptations already made by plants within the school garden ecosystem.

Please read the following effects on school gardening keeping in mind the possibilities for science observations and experiments. Students must, in a sense, become soil scientists and plant biology researchers, observing and tracking weather and its impacts in the garden.

EFFECTS OF TEMPERATURE VARIATIONS

Heat Stress in the Garden (photo by Maureen Gilmer)

Heat Stress in the Garden (photo by Maureen Gilmer)Greater warmth can increase growth rates or mature plants earlier (putting plants on "fast forward"). But then unseasonable weather events like late frosts can weaken or harm that new growth.

High heat (above 35ºC or 95ºF) or low temperatures (below 5ºC or 41ºF) can slow or stop photosynthesis! During heatwaves, plants use up their sugars faster, making them bitter or less flavourful.

Higher temperatures can also ruin pollen (so fruits don't set) or cause other plants to bolt and set seed sooner. (Greenhouses can easily become too hot for the flowers of heat-loving plants such as tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers.)

Higher temperatures encourage more generations of pests in one growing season. (Watch out for higher numbers of codling moth, carrot rust fly, cabbage root maggot, beet leafminer, fruit flies, and aphids.)

Sunscald (damage to plant tissue caused by exposure to excessive sunlight) is more common now and can be seen on flower leaves, fruit and berries, and the leaves of vegetables. The heat of direct sunlight also inhibits ripening in some veggies, such as tomatoes and peppers (look for green or yellow "shoulders").

Late spring or early autumn frosts or snowfalls can injure plants, especially when unseasonably warm spells have caused them to bud earlier than usual or the plants aren't yet acclimatized.

Plants can adapt to higher or lower temperatures, but not to rapid swings between the extremes.

Heat-Affected Tomato (photo by Doreen Greve)

Heat-Affected Tomato (photo by Doreen Greve)Temperature extremes can also lead to growth anomalies through disorders in the way that plants flower before fruiting. Picture cabbages that don't form a head, or strange-looking tomatoes.

Plants stressed by heat and drought can't absorb calcium from the soil (not necessarily due to a soil deficiency), resulting in damaged plant tissue that is often mistaken for disease.

EFFECTS OF CHANGES IN PRECIPITATION

Plants can be resilient to moderate drying, but not to severe drought. Cellular processes are disrupted by dehydration.

Plants can also adapt to moderate heat or drought, but not to both together. This combination can stop photosynthesis, meaning that plants aren't getting food to help them grow.

When the soil is dry, nutrients can't pass into plants because they need a film of water around their roots; the tiny root hairs then dry out and die. Root damage then leads to nutrient deficiencies, poor growth rates, and susceptibility to diseases and pests. Perennial plants with root damage are also more vulnerable to drought next season.

Soil During Drought (photo by Shutterstock/Condor 36)

Soil During Drought (photo by Shutterstock/Condor 36)When there is no movement of water up from the roots, plants can't transpire, which raises the temperature of their leaves, killing leaf cells.

Aphids thrive on drought-stressed plants. And boring insects attack trees that have been weakened by poor growing conditions.

A change in precipitation can also mean higher rainfalls, which can flood garden beds or cause waterlogged soil. Waterlogging injures or kills roots.

When school closures over the summer make regular watering difficult, but summer rainfall is no longer regular or predictable, fruits like tomatoes can suffer from blossom end rot. (It's from a calcium deficiency in the plant tissue, usually from irregular watering.)

In both cases (drought and flooding), fruit-laden trees are more liable to be uprooted and topple over in high winds.

Climate Change Strategies for School Gardens

Again, most of these tips are from Linda Gilkeson, with thanks.

• Help your students learn how "weird weather" affects plant growth. Have them keep records, especially of varieties that do well in extremes.

• Temperatures can be hotter and colder than expected — and sometimes happen at unexpected times. Be prepared for temperature swings, heatwaves and cold snaps by having shade cloths, row covers, tarps, plastic sheets, and/or cloches (which can be made from milk or juice jugs) handy. Seedlings might need to be protected by a layer of newspaper or burlap. You can also cut pre-fabricated lath fence panels to fit over your beds to serve as instant shade covers.

You might even want to have some fun doing drills with your students so that these can be set out quickly based on weather forecasts. (Of course, the students can be responsible for checking the forecasts daily and before weekends and holidays.)

• All year round (but especially during heatwaves), have your students plump up thick mulches around large plants and sprinkle fine mulch around seedlings to keep the soil cool. Mulches can include leaves, lawn clippings, compost, garden waste / crop residue (chipped up), straw.

• When it gets hot, be sure to use shadecloth over your greenhouse, polytunnels, seedling beds, and cool weather crops: peas, lettuce and other greens, cabbage family). Open all the days and windows of your greenhouse (if they don't open automatically). Consider installing more vents or using a fan to move air around.

• Water plants in the morning to reduce afternoon evaporation. (Before-school Garden Club, anyone?) That way, their roots have water throughout a hot day but the leaves are dry by evening, which can help avoid diseases. Do infrequent but deep watering to ensure healthy, deep-rooted plants. Increase watering during heatwaves, if possible.

• Have your students map out which parts of the garden are more exposed and therefore dry out faster, and which areas retain moisture better.

• If you and your students garden in containers, keep in mind that roots don't tolerate as much heat as foliage can — don't plant in metal containers! (And wrap black pots in white fabric to keep the roots cooler.) You will have to water more frequently with heat, low humidity, or winds. But check each pot individually as each plant's water needs will vary. Smaller pots, as well as unglazed / terra cotta pots, dry out faster.

• Prepare for heavy rainfall events by improving soil drainage to prevent waterlogged soils, especially around perennials, shrubs and trees. Build raised beds for veggies and strawberries. Keep your soil covered with living plants and mulches to protect soil from erosion during heavy rains.

• Prepare for strong winds by bracing tall and top-heavy plants, such as tomatoes, corn, and the brassicas. Install strong trellises for vining plants such as peas, pole beans, grapes and kiwis. Stake dwarf fruit trees throughout their lives, including temporary supports for fruit-laden branches.

Tomatoes Growing Under a Polytunnel (photo by Linda Gilkeson)

Tomatoes Growing Under a Polytunnel (photo by Linda Gilkeson)EXAMPLE: CLIMATE CHANGE STRATEGIES FOR TOMATOES

• In hot, dry weather, keep fruit shaded by minimizing pruning of leaves. Pay attention to watering (tomatoes usually like less frequent but deep waterings, but you might have to water more often). Mulch the soil around the tomato plants. If temperatures rise above 32ºC (90ºF), use shade cloth to prevent the loss of tomato flowers. (Remember, high heat ruins pollen.)

• If the growing season is cool and wet, prune the tomato leaves to provide good air circulation and to promote ripening. Grow the tomato plants in a greenhouse or polytunnel. And be sure to keep the leaves dry when watering to prevent blights and other diseases.

• Design your school garden to be as protected as possible from weather extremes. Windbreaks, walls and solid fences will protect plants by ensuring they are less exposed to wind and cold. Plan to include water storage and an irrigation system. A large amount of rainwater can be collected from the small roof area of a garden shed.

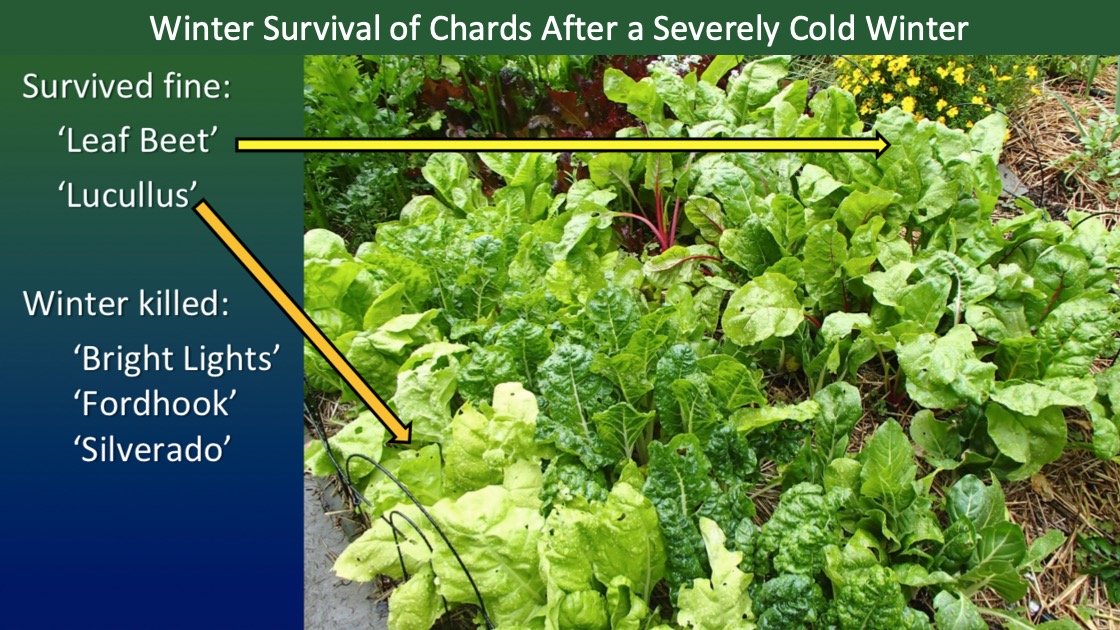

• Choose plants and cultivars of plants that are resilient, and that require less water in the summer. (Yes, you might have to give up on tomatoes in your school garden. Or choose cherry tomatoes, or varieties with small- or medium-sized fruit.) Grow more than one variety of each crop. That way, your students will have more chance of success.

• Perennial plants are less vulnerable to wacky weather than annuals are. Once established, they are much hardier and need less water.

• Include resilient native species that also attract pollinators, as well as drought-tolerant ground covers.

• Learn about the insects that visit your garden. Have your students figure out which are beneficial, and which are destructive to the crops you've planted. Plant flowers to attract the beneficial insects (they might even do double duty as pollinators).

• If you can (in a greenhouse, cold frame, or polytunnel), plant cold-hardy crops in the fall, in order to reap spring harvests. Overwintered plants grow quickly in the spring, and survive poor weather, late frosts and spring pests far better than spring-sown seedlings do. That will give your students food to eat from the garden from March until June.

(photo by Linda Gilkeson)

(photo by Linda Gilkeson)Cold-tolerant crops include:

- Leeks

- Onions and shallots

- Garlic

- Parsnips

- Turnips

- Broad beans

- Greens like chard, perpetual spinach, and kale

- Radishes

- Cabbage and brussels sprouts

- Broccoli and winter cauliflower

- Carrots

- Beets

- Asparagus

- Christmas potatoes

- Kohlrabi and celeriac

- Winter squash

• Secure your school garden when school isn't in session. While it's nice to imagine schoolyard "visitors" (of the two-legged and four-legged varieties) enjoying a wee walk through the garden, sometimes they will take food that your students have worked hard to grow. (Alas, before I reluctantly put a lock on our school garden gate, our maintenance person came across "tourists" walking to the school parking lot ... their arms laden with produce my students could have enjoyed.)

More and more now, let's ensure that visitors don't undo what's been set up to counter climate change impacts (by perhaps tripping over irrigation hoses, tampering with automatic greenhouse window openers, or disturbing shade cloth or mulches).

• Build your own mulch sources into your garden design. The best mulch is compost or leaf mould, but you can also use shredded newspapers or straw / cut grass (ask the person who mows the school's yard to collect the grass for you). One year, the local garden club invited some of my students to make a presentation about our school garden — and thanked us with very much appreciated bags of leaves they'd collected (our schoolyard had very few deciduous trees).

• Ensure that greenhouses don't become too hot for the flowers of heat-loving plants such as tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers. This is tricky on weekends and during holidays, so install heat-activated window openers.

• Adapt your seeding methods to suit current weather conditions (rather than what you've traditionally done). In spring or cool weather, don't sow seeds until the soil is above 15ºC (59ºF); cover it with a sheet of clear plastic to warm it, if necessary.

• In summer or hot weather, sow seeds slightly deeper and keep your seed bed shaded until germination. (Keep in mind that the soil might be too hot for germinating carrots, lettuce, parsnips and corn salad.)

• One vital aspect of gardening in unpredictable weather and a changing climate is adding more organic matter into your soil. Use leaf mould or compost, and leave plant roots in the ground when harvesting.

Linda Gilkeson, PhD Entomology

Linda Gilkeson, PhD EntomologyBuild soil organic matter. Humus (well-digested organic matter) improves soil structure, water-holding capacity, and nutrient availability. It stores nutrients in a slow-release nutrient “bank,” preventing nutrients from leaching away in heavy rains. Organic matter also holds carbon in the soil.

Be prepared for hot/dry weather, cool/wet weather, extreme cold, heat, rain, wind or whatever is coming next....

One way to figure out what will grow in your "new normal" climate (wetter, drier, hotter, colder) — except that climate variability is the new "normal" — is to learn what is grown in environments that already have those particular climatic conditions or climate type. Besides the Plant Hardiness Zone Map, you can also check "analogous" climates on the Köppen Climate Zones map.

Learn the principles and practices of permaculture and regenerative agriculture, even on a small scale.

Finally, remember that Indigenous people and nations around the world have been growing food where they live for millennia, despite regional climate changes. Learn about the traditional uses and current roles of Indigenous plants within the local culture and ecosystem, and the importance of these plants in environmental restoration. (With thanks to Sarah Jim and the Victoria Compost Education Centre for a fascinating and heartwarming Ethnobotany Walk, 2022.)

All our relations.

Regenerative agriculture is rooted in land justice. Not only shifting toward land access and land sovereignty for communities of color and Indigenous people, but also in that process allowing communities to bring back forms of relating to the land better, more reciprocally.

Land is a living being that you have a relationship with that involves responsibilities as well as things that the land offers you. It’s about the whole society seeing land as a relation.

— Liz Carlisle, author of Healing Grounds, a book of stories of Indigenous, Black, Latinx and Asian American farmers who are using their ancestors' farming methods to restore health to ecosystems and revitalize cultural ties to the land

Traditional Three Sisters Garden (Haudenosaunee)

Return to Climate Change Strategies for School Gardens

Go to The Value of School Gardens

Visit the GreenHeart Education Homepage