Nature Journals in Sustainability Education are Transformative

Help your students develop the habit of keeping a Nature journal. Nature journals in sustainability education are a way for young people to learn about the rest of Nature in a transformative way.

Nature journaling is also an opportunity to integrate language arts, science and art while developing students' observation, writing and artistic skills.

This is no small thing. It's a lifelong gift you'll be giving

your students.

Nature journaling is a proven way to help children become aware of the environment around them and to develop their sense of connection with it.

— Karen Matsumoto, in The Nature Journal as a Tool for Learning

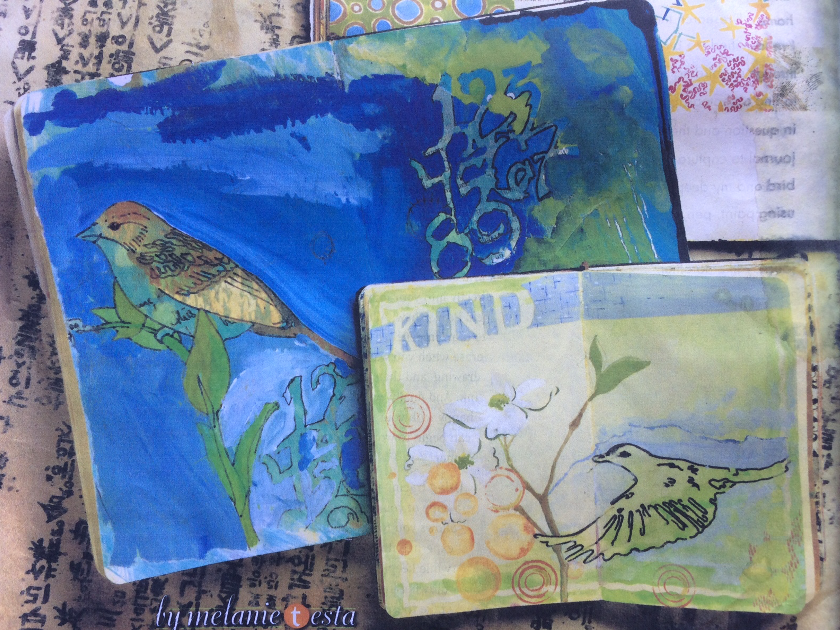

Beautiful Nature Journals Created by Melanie Testa

Beautiful Nature Journals Created by Melanie TestaWhat is a Nature Journal?

There are lots of names for a Nature journal: diary, daybook, almanac, logbook, chronicle, field notes.

It can be a simple scrap of paper, a small booklet, or a stunning collection of pages awaiting your students' entries.

A nature journal is the regular recording of perceptions and feelings about the natural world. It is a place to record observations about one's experiences outdoors, in note form and as sketches or paintings.

Nature journalling is a great excuse to get your students outdoors; to help them slow down and connect with the rest of Nature; and to increase their observation, writing, drawing and reflection skills.

It can be used for cross-curricular projects or to go deep into Nature study — one antidote to screen time and growing anxiety and depression in children and youth.

Walking in the woods, journal in hand, and finding a great place to sit and draw a beautifully fragile flower is a wonder and a joy. My journals help me to interpret and become one with my surroundings, and present opportunities for me to learn and expand as an individual.

— Melanie Testa

Logistics of Nature Journals in Sustainability Education

Organize your class schedule so that students get "academic" outdoor time regularly (15 minutes each day, or half a day per week, or at least a full-day nature excursion once per month or season, including in winter).

Give each student a blank journal or have them create and personalize their own, perhaps using "rescued" paper or paper that you make with your class.

Journal together as a class before going outside. Make a mind map or web of the kinds of trees, shrubs, flowers, clouds, weather, insects, birds and other animals you will likely see in the schoolyard or local park.

Give your class short observation periods to start with, then increase the time as student interest and ability to focus increases. It takes practice to become an effective Nature journaler.

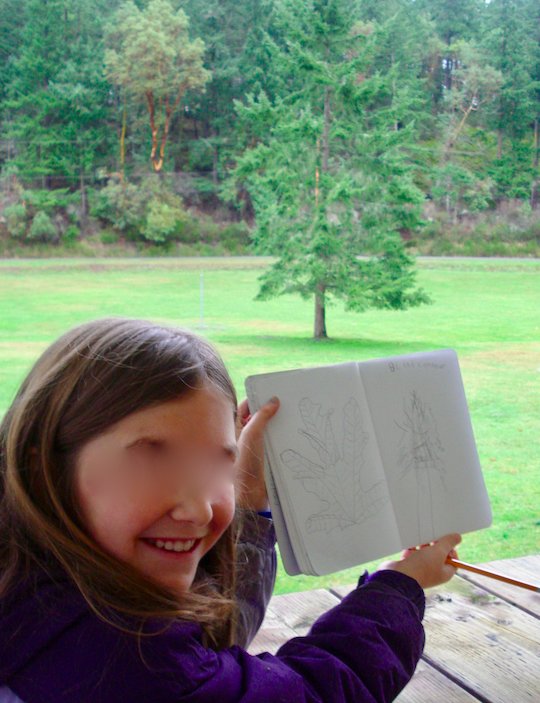

Students Journaling in the School Garden

Students Journaling in the School GardenBefore heading outside for the first time (with review before the next few sessions), show students how to make good field notes (for scientific rigour) in order to identify unfamiliar plants and animals once they come back inside:

- Include the date/time/place, weather, moon phase, and sunrise and sunset times, according to Clare Walker Leslie.

- Write what you observe, starting with the general and then the details — as well as what's missing or, perhaps more accurately, what you're not seeing.

- Describe using comparisons rather than precise measurements — especially for animals, which don't sit still like plants do.

- Pretend you are describing your subject to someone who has never seen it before; look for key features of the observed plant, animal or rock ("the colour of the various body parts, including the beak/snout and the feet, of animals; the shape of the leaves and the pattern of the veins of plants; the features of the wings and type of antennae for insects" — Ann Nightingale in The Victoria Naturalist).

- Make notes about the environment or the habitat of what you're observing.

Student Journaling in the School Garden

Student Journaling in the School Garden- Use all your senses (well, probably not your sense of taste!), noting a scent, a texture or a sound. For example, was it a vocal noise, or the sound of wings flapping? Was it a sweet smell, or noxious?

- Note behaviour for both animals and plants. (Was the flower facing the sun? Did the bird walk or hop? Did the insect fly straight or zigzag?)

- Draw a sketch. (It doesn't have to be an artistic masterpiece.)

- Check with field guides and ID books once back in the classroom to identify any new "friends" or neighbours.

Nature journaling offers a unique pathway to intertwine our human narratives with the ever-unfolding stories of the natural world. In a world that moves at a relentless pace, it’s easy to overlook the exquisite wonders that surround us — the delicate unfurling of a fern, the vibrant flash of a bird’s wing, the whisper of wind through leaves.

— Kristen Webb Wright

How to Give Students the Gift of Nature Journals in Sustainability Education

Teachers can contribute to transformative sustainability education through Nature journals by:

• starting with a sensory awareness scavenger hunt, with items on the list depending on the season (for examples, see Amanda McCoy's Hearts and Trees; or try an Unnatural Trail)

• encouraging students to find a regular Magic Spot (a quiet place to sit "alone" with the rest of Nature for a bit of time) when you take them outdoors (make sure each one is within your sight)

• studying famous natural journal keepers:

- Charles Darwin

- John James Audubon

- Maria Sibylla Merian

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Rachel Carson

- Gilbert White

- Edith Holden's Diary of an Edwardian Lady

- Wilson Bentley ("Snowflake Man")

- Louis Agassiz

- Jean Henri Fabre

- Marc Catesby

- Anna Botsford Comstock

- Henry David Thoreau

- Ernest Thompson Seton

- John Muir

- Beatrix Potter

- Roger Tory Peterson

- William Bartram

- Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

- Margaret Morse Nice (who became a song sparrow expert)

- Thomas Jefferson (former United States president)

• keeping track, as a class, of plants and other-than-human animals in the schoolyard or nearby park (if there are no actual sightings, record evidence that they've been there)

• studying Nature's patterns together in class and then getting students to draw and/or describe any natural patterns that they observe outdoors

Different Patterns in Nature for Students to Look For

Different Patterns in Nature for Students to Look For• inviting a local ornithologist ("birder") or other naturalist to talk to your students about the exciting hobby of keeping life lists (remember that fun Hollywood comedy, The Big Year?)

• encouraging students to become both scientists and artists through their Nature journals (developing both critical and creative thinking skills and an inquiring mind)

• sometimes taking props outdoors, such as ID books, binoculars, magnifying glasses, digital cameras or bug boxes (but be sure to let any captured creatures go before heading back inside)

• occasionally giving students a focus (draw and describe a seasonal change that you see; "draw" and describe three sounds that you hear; compare two rocks in images and writing)

• encouraging students to include:

- descriptive, creative and/or reflective writing

- sketches and drawings (and maybe some watercolour paintings)

- dates and locations

- weather conditions, moon phases

- species identification

- quotes, poems and stories (of their own and others)

- photos, videos or even audio recordings

- personal reflections

- (with thanks to Kristen Webb Wright for these ideas)

How to Assess and Evaluate Nature Journals in Sustainability Education

Children need to know the names of the cast members in the play called Life. Environmental education typically concentrates on the big picture of ecological roles, functions, habitats, relationships and patterns, but children also need to know who the 'players' are.

— Robert Michael Pyle, naturalist and writer

Pride in Her Sketching

Pride in Her SketchingHave students write field notes for species they already know (for example, common birds or trees) to see if they have set up their journal properly — and what more they can learn.

Provide feedback (preferably on a sticky note: a positive, encouraging comment + a question to get the student to think more deeply).

Discover as a class all the many species of plant and/or animal in the schoolyard or local park and then create ID cards together — a class set, and perhaps a family set for each student.

Get students to share their journal entries when you are back in the classroom.

Don't "mark" the journals unless you have told students exactly what you will be looking for. A journal should be a safe space for creativity and experimentation in writing and art.

"Don't ignore simple, anecdotal observations of [Nature journalers] in the act of keeping their journals. Often these informal statements of recognition, awe, and appreciation are just as valid and reliable an indicator that learning is going on as are more formal tests and measurements." (Clare Walker Leslie)

Pull observations from student journals to decide on a teaching focus. (For example, do all bird beaks look the same?) After your students find the answer, you can facilitate an inquiry project (in this case, into bird beaks, how they differ, the specific purposes they serve, such as eating different types of foods, what else a beak might be used for, like serving as an arm, etc.) (With thanks to Jennifer Ward in I Love Dirt!)

Outdoor Safety and Classroom Management Strategies for Nature Journalling

There is no such thing as bad weather, only inappropriate clothing and lack of preparation.

— Steve Dunsmuir, Saturna Ecological Education Centre

Sketching "Wildlife" on a Wet Day

Sketching "Wildlife" on a Wet DayAsk parents to ensure their children are suitably dressed for the weather.

On terribly cold, wet or windy days, bring an object into the classroom for students to draw, write about, and research. Have ID books in your room or go to the library. (Note that it's never wise or safe to go near trees in high winds.)

Make simple sit-upons (extra-large Ziploc bags with folded up newspaper inside to sit on) to keep pants dry on wet days. Keep some extra hats and mitts in your backpack. (With thanks to Jaclyn Fink for these "overcoming the weather" suggestions.)

Always carry a first aid kit (and know how to use it). Determine a "home base" outdoors and make sure everyone knows where it is.

Take a whistle, but practise your signals ahead of time, perhaps as a game in the schoolyard. One long blast means finish your sentence or diagram and come on back. But three long blasts means come right away! Determine together whether your class will need any other signals.

When talking with your class outdoors, always be the one facing the sun. Never make your students look up into the sun when listening to you. Make sure that students wear sunhats to protect their eyes.

Remind students each time that journaling is a quiet, reflective activity, and then set the example by journaling along with them (in your own Magic Spot with a view of every student's special place).

Create a ritual (together) for getting to your Magic Spot area. Will students need to let off steam along the way, or become quiet and contemplative? Perhaps play an "ambulatory" (walking) game of I Spy, getting students to look for something red or listen for rustling leaves or find a waxy leaf.

Resources for Nature Journals in Sustainability Education

Keeping a Nature Journal: Discover a Whole New Way of Seeing the World Around You, by Clare Walker Leslie (the North American guru on nature journals) and Charles E. Roth, is a delicious exploration of all thing nature journal — ideas and suggestions, gorgeous artwork and sample entries, and assessment and evaluation recommendations for teachers.

John W. Brainerd's The Nature Observer's Handbook: Learning to Appreciate Our Natural World helps us to see both Nature's patterns and people patterns.

Introducing your students to keeping nature journals in sustainability education is a lifelong gift to them. Your students will become more curious, more inquiring, more patient, more observant, more skilled at research, art and descriptions, and more attuned and — we hope — in love with the rest of Nature.

Return to Transformative Nature Study

Visit Great Naturalists

Learn about the Naturalist Intelligence

Return from Nature Journals in Sustainability Education to

GreenHeart Education Homepage